At CES (Consumer Electronics Show) 2026 in Las Vegas, a man sits blindfolded in a self-driving personal mobility chair as it calmly navigates a crowded convention hall. Around him, a LiDAR-equipped, voice-controlled scooter threads its way through clusters of staring visitors, while an autonomous robotaxi announces its arrival not with a horn, but with glowing LED initials projected from a halo on its roof.

None of it feels futuristic in the old sci-fi sense. It feels oddly casual, almost playful.

For the first time since the early 2020s, electric vehicles took a back seat at CES, while autonomous vehicles (AVs) surged ahead. Across convention halls and demo zones, the message was unmistakable: the driverless age has become a reality. The question hanging in the air was whether 2026 might be the breakout year for robotaxis.

But while Las Vegas hosted the spectacle, the real testing ground lay elsewhere: on ordinary streets, amid pedestrians, reckless drivers, delivery trucks, and in general, unpredictable human behaviour. To understand what this future feels like when it collides with daily life, I go not to a convention hall but to two cities quietly living inside the experiment: Austin and Las Vegas.

Austin skyline

| Photo Credit:

Nitin Chaudhary

From convention halls to city streets

My sojourn starts one evening in Austin when I bump into Jeff, a local guide, as he walks down South Congress Avenue with his cohort. “This is the most Instagrammable mural in Austin,” he says, pointing to a bland peach-coloured wall graffitied across which, in red, are the words ‘I love you so much’.

“The most Instagrammable mural in Austin”

| Photo Credit:

Nitin Chaudhary

I tell him that I am visiting from Dallas to study the AVs that seem to be crawling all over the city. Jeff looks up to ask: “And did you risk getting into one?”

“Yes, I did. Many times,” I reply. I had spent the whole day stepping in and out of Waymo robotaxis (more on that later).

Jeff looks surprised at my audacity to ride in a vehicle that drives by itself.

“On these Texan streets!” he exclaims. “I drive a truck, and I still feel unsafe!”

I mention offhandedly that I felt safe riding in these vehicles.

“Till they’re not…!” Jeff says, waving goodbye.

Indeed, not all the signals have been reassuring. Recently, a Waymo robotaxi struck a child near an elementary school in Santa Monica, triggering a federal safety investigation. The child sustained minor injuries, but the incident serves as a reminder that even today’s most advanced autonomous systems can struggle in complex, unpredictable environments such as school zones.

Navigation panel in a robotaxi

| Photo Credit:

Nitin Chaudhary

Autonomous tech

Autonomy is spreading far beyond passenger cars. For instance, robotics and AI-enabled machinery are transforming heavy industry and construction. Today, autonomous excavators, bulldozers, and earth-moving equipment use sensors, GPS, and real-time algorithms to perform tasks with minimal human intervention, boosting productivity and safety on worksites. At CES 2026, Caterpillar Inc. unveiled a new generation of autonomous construction machines designed to change how work gets done on jobsites.

Test bed for autonomous cars

Austin has rapidly evolved into one of the biggest tech hubs in the U.S., attracting big names, including Meta, Google, Oracle, Tesla, Snap, and Apple. If government initiatives to boost growth outside traditional centres draw companies to Austin, the promise of lower costs of living, cultural openness, job surplus, and flexibility to work remotely post-pandemic have seen tech workers flock here from Silicon Valley.

Austin is also where many AV companies are testing their fleets. At least three — Zoox, Tesla, and Waymo. I am determined to try them all.

Market size

Estimates vary widely since autonomous driving is still a nascent market. According to U.S.-based Grand View Research, the global autonomous vehicle market is projected at $86.3 billion in 2025, and is expected to reach $214.32 billion by 2030.

But where can I spot one? The hotel receptionist directs me to Rainey Street, a residential neighbourhood turned laid-back nightlife hotspot. On a Friday night, the boundaries between where the eateries end and the road begins have blurred. Vehicles navigate this confusion carefully, moving in gentle hiccups.

“Look!” my partner points. It is a Tesla with a vacant driver’s seat. A person is in the front passenger seat, carefully monitoring the surroundings, ready to take over in case the car does something funny. I stand gaping as the car slickly navigates the pedestrians around it.

Spotting a tesla

| Photo Credit:

Nitin Chaudhary

The next morning, as I sit at breakfast, I spot a Chinese-origin man at the next table wearing a Tesla T-shirt. Michael turns out to be a Tesla employee of seven years. Over bland coffee and crusty muffins, I describe to him my first encounter with a driverless Tesla.

“You’ll see more of those in the coming years,” says Michael. “But did you notice that the RoboTaxi logo was scratched off the car?”

I hadn’t. I ask him why.

“That’s because we were seeing a backlash. Both against Elon Musk, given his political affiliations, and against our driverless cars in general. So, Tesla started removing the RoboTaxi logos. Otherwise, people were hitting these cars.”

I later learn that many in Austin have expressed fears about the reliability and safety of autonomous vehicles, particularly Tesla’s, which have reportedly failed to stop at hazards or stop signs. But I am still determined to ride in one.

Riding a Tesla RoboTaxi requires prior registration. Ours hasn’t come through. So, we decide to hail the next best alternative, a Waymo robotaxi.

Alphabet’s autonomous driving division, Waymo began testing in Austin as early as 2015. It now operates several fully autonomous, all-electric Jaguars across roughly 90 square miles of the city.

The Waymo cars are white sedans with a large spinning unit on top, which is a 360-degree Light Detection and Ranging sensor (LiDAR) that uses laser beams to create a detailed 3D map of the surroundings. I order one through the Uber app. It arrives and neatly parks beside me. I unlock it and begin the trip entirely through the app. Inside, it is luxurious and quiet. Through the interface, I direct the car to start, and once it does, it feels like being in a normal taxi, except for the missing driver. The steering wheel twists and turns as the vehicle follows the route displayed on a large screen in the middle of the dashboard.

A Waymo car

| Photo Credit:

iStock/Getty Images

It seamlessly merges into Austin’s traffic. Locals don’t even turn their heads when one passes. By the end of my two-day Austin stay, I have taken eight Waymo rides, feeling secure in each.

Safety first

India remains at an early stage. The country’s autonomous vehicle market is projected to grow to about $11.37 billion by 2030, according to Grand View Research. Much of this growth reflects the broader AV ecosystem. Progress is most visible in the spread of semi-autonomous safety features, with models from Mahindra and Tata offering tech such as adaptive cruise control.

Two paths to autonomy

After the CES conversations and my first encounters, I reach out to Chinmay Chaudhary who works at Stellantis, the parent company of brands such as Jeep, Chrysler, etc. He offers a grounded, industry-facing perspective on why AVs behave so differently depending on who builds them.

When I describe my Waymo rides, he immediately frames them not as a technological marvel but as a business model. “Waymo is more of a fleet ownership model. You can only avail it in specific towns where they run currently,” he says. In other words, Waymo doesn’t sell autonomy to individuals. It deploys it selectively, city by city, street by street. That selectiveness, he explains, is precisely why the experience feels so polished. “Waymo is specifically based out of a geofence network. It performs better in a closed vicinity where everything is mapped.” Seen through that lens, it makes sense that the Waymo is executing on a script rehearsed endlessly on Austin’s streets.

Inside a driverless cab

| Photo Credit:

Nitin Chaudhary

This contrasts with Tesla’s approach, Chaudhary points out. “Tesla’s is like a personal ownership model. You can buy the car out of the showroom and start using it,” he says. Where Waymo centralises risk and control, Tesla distributes it by placing experimental autonomy directly into the hands of individual drivers and onto unmapped streets. That openness may explain both Tesla’s scale and the anxiety surrounding it. “It’s not that one technology is better than the other,” Chaudhary cautions. “It’s how well you master it.”

Beyond Austin

While in Austin, I spot a few Zoox cars, which are Toyota Highlanders retrofitted with radars and cameras, each with a safety driver, just like Tesla’s AVs. Founded in 2014, Zoox was acquired by Amazon in 2020, bringing yet another tech giant into the self-driving race.

Legacy automakers across the world have been quietly building their own paths to autonomy. Mercedes-Benz, for instance, is rolling out autonomous driving in the U.S. this year, using Nvidia Drive AV, an AI software, allowing drivers to take their eyes off the road under specific conditions. Nissan has been testing autonomous mobility services in Japan, while Baidu already operates large scale robotaxi fleets across multiple Chinese cities.

The technology remains expensive, with the sensor and computing stack on each vehicle estimated to cost about $100,000 over the car’s base price. Still, there is a growing sense in the U.S. that it is now in a race as China’s AV sector is outpacing competitors in deployment speed.

As an Indian in America, I find myself thinking about the many Indians shaping this industry from within the U.S. Ashok Elluswamy, vice-president of Tesla’s AI software, has come under online scrutiny for arguing that the “obvious” solution to Tesla’s long-running self-driving challenges lies in its camera-only approach, dismissing the need for additional sensors such as LiDAR. At Uber, another Indian, Balaji Krishnamurthy, has stepped in as chief financial officer, taking over from Prashanth Mahendra Rajah, at a moment when robotaxi investments are moving from experimentation to execution.

“Zoox is taking different approaches in different cities,” Michael, the Tesla employee, tells me. “In Austin, it’s retrofitting vehicles and is still in testing mode. But if you want to see the full promise of Zoox, go to Las Vegas.” I am intrigued enough to do that.

Zoox began testing retrofitted vehicles near its Las Vegas headquarters in 2019. It took a bold new route in 2023 by launching futuristic, purpose-built robotaxis. Last year, it officially launched its public robotaxi service. It currently operates on limited stretches of the Strip, offering a controlled environment with predictable traffic. Rides are free for now, with Zoox offering the service at no cost while it gathers real-world feedback and awaits approval to begin charging passengers.

At one of five pickup spots where Zoox cars can be hailed, I wait. Soon, a minivan-shaped vehicle rolls up. It drives bi-directionally, meaning it has no front or rear. Its sliding doors, designed to minimise the risk of hitting nearby objects, opens to reveal a four-seater layout.

After I’m seated, the car doesn’t budge. It keeps reminding me to fasten my seatbelt, though I already have done so. Then, a human voice comes through a speaker on the roof. “I suggest you remove the bag from the seat. It’s interfering with our sensors,” the voice says. I do so, and the car starts to move.

Waymos on the street

| Photo Credit:

Nitin Chaudhary

“Do you monitor what happens inside the car?” I ask.

“No, not always. Only when there’s an issue,” the faceless voice says.

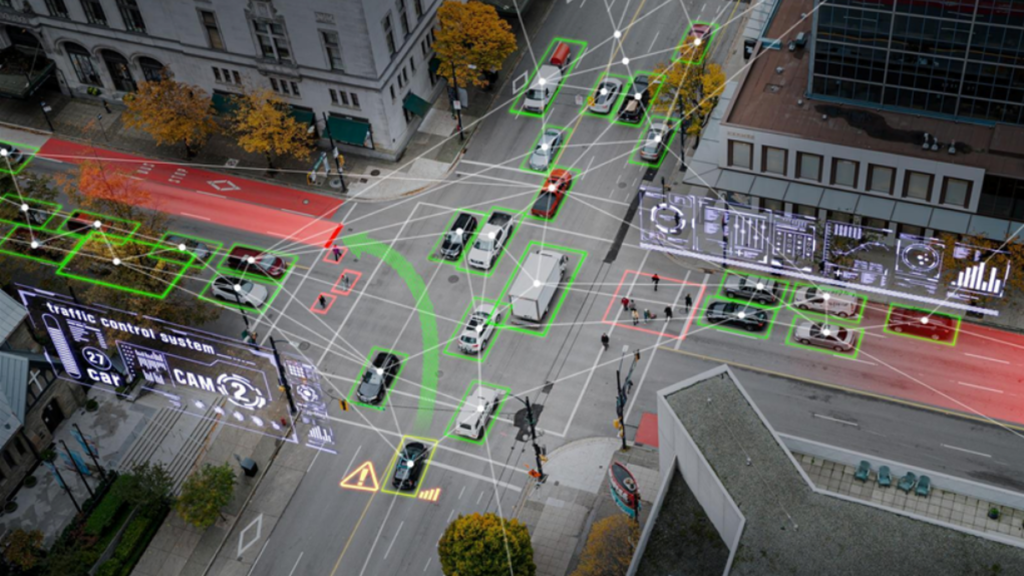

This realisation is discomfiting. To function, these AVs need a view of the streets, sidewalks, and the people moving through them. It is, in effect, a kind of god’s-eye vision. Always on, always watching. These cars are also recording and retaining visual and location data. How long that data lives, who controls it, and under what circumstances it can be accessed and by whom remains murky. Without clear guardrails, these AVs risk becoming mobile surveillance systems.

The Zoox car starts to move gently. No hiccups, no jolts. Unlike the retrofitted cars, it has no steering wheel or pedals, just the smooth confidence of a system built from scratch. Zoox completes a five-mile loop and brings me back to where I started.

Look East

In China, autonomous and semi-autonomous technology has already reached scale. Data from the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology shows that advanced driver assist systems were present in about 62.6% of new passenger cars sold in the first half of 2025.

In the long run

In Vegas, another vision of the future is unfolding 40 feet below ground. The Vegas Loop, a network of narrow tunnels (roughly 12 feet wide) dug by Musk’s Boring Company, now shuttles passengers between stations in Tesla vehicles. At one Loop station, accessed via an elevator, I watch a neat line of Teslas picking up passengers and shooting off into the tunnels.

Rodrigo comes to pick me up in his Tesla Model S. He eagerly explains to me Musk’s vision: the Boring Company would build the infrastructure, and Tesla taxis would run through it. “The long-term plan,” the taxi driver says, “is to transition the Vegas Loop to fully autonomous Tesla robotaxis. We won’t need human drivers then.”

“What about your job, and those of other drivers?” I wonder aloud.

Rodrigo shrugs. It is a shrug of uneasy acceptance. The silence that follows lasts less than a minute; my stop arrives under 10 minutes and costs less than $5, a trip that would have otherwise taken 30 minutes in surface traffic.

I emerge from the tunnel into the chaos of Vegas. My journey is coming to an end. Despite all the warnings and fears of jobs being lost, I feel strangely optimistic. It is a future that holds the promise of a frictionless-commute world. As Stellantis employee Chaudhary put it earlier, the question is no longer which technology is superior, but who will master and scale their chosen path first.

The writer is a U.S.-based professional with an interest in travel and culture reporting.